Jean-Michel Basquiat: Transforming the Modern Art World

- Meri Utkovska

- Mar 7, 2024

- 18 min read

Updated: Jan 29

"I cross out words so you will see them more; the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them."

-Jean-Michel Basquiat

I love Jean-Michel Basquiat. Not because he used those striking shades of blue in his paintings that make me think of clear skies and open oceans, nor because of his dichotomic poetical compositions and immediate, musical way of creating - those are obvious, and perhaps, easier reasons to love him, for which I certainly do. I love Jean-Michel Basquiat, however, predominantly because of his humanity - referred to, here, as a way of observing the world and making a conscious choice how to be a part of it.

Basquiat lived, though terribly shortly, with a fervent conviction of being an artist, and a romantic notion of deserving to become famous for it. Inwardly, he knew exactly who he was. Outwardly, he became precisely that. One cannot enter Basquiat's world without realising the contrasts of universal existence - the single line with a south and a north, the sphere with a sunrise and a sunset. One cannot, as well, deny that his mere existence was a form of rebellion - rising to be one of the most important Black artists in a White-dominated elite art world, which, however welcoming and hungry it might have been for his art, did, eventually, contribute to his death.

There is no growing up in Basquiat's paintings. There is youth, yes, and there is death. There are boys, and there are skeletons. There is poetry and jazz, philosophy and film.

There is him - the boy who never grew up.

And, if you ever stand in front of a Basquiat, you can still hear that boy, singing.

Early Life, Pop Art, and Gray’s Anatomy

Born on December 22, 1960, in Park Slope, Brooklyn, New York City, Jean-Michel Basquiat was the son of Matilde and Gérard Basquiat. His mother, to whom he was very close, loved art and often took him to art museums. She would draw and sketch with him, and, seeing how gifted her son was, encouraged his artistic talents. Basquiat grew up in the midst of change - the art world was changing as much as his own life. The sixties were a time when Andy Warhol's Campbell's soup cans, put on display in the window of Bonwit Teller and in the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, marked America's consciousness.

The whole idea of advertising was changing, hungry for the Pop Art movement, which placed mass media as both its core subject and its method of distribution. "Pop art took the inside and put it outside, took the outside and put it inside," wrote Warhol in his POPism.

The sixties were also a time of emergence for an entirely new breed of collectors, such as Robert and Ethel Scull, who became avid collectors of the new art. Scull loved to discover art on his own, often buying the works right out of the artist's studio. They threw huge parties at their home on Long Island, because they liked to socialise with the artists they collected - setting the path for the collectors of the eighties, who longed for an odd kind of high produced by being in the presence of the Artist. In 1969, Basquiat, only nine at the time, was hit by a car while playing on the street. He suffered several internal injuries and had to have his spleen removed. To keep her son occupied while being hospitalised, his mother brought him a copy of Gray's Anatomy. The book fascinated him. Its lasting impression can clearly be seen in his later work - anatomical drawings and prints, as well as the name of his band, Gray. Basquiat's parents separated later that year, and he and his sisters lived with his father, who was a very strict figure. A few years later, when he was eleven, his mother was committed to a mental hospital.

Al Diaz, SAMO and the Romance of Stardom

Basquiat was an angry, mischievous and rebellious child. He moved from school to school, and in 1976, he was transferred to City-as-school, a progressive school in Manhattan. Designed for gifted and talented children who find the traditional educational process difficult, City-as-school is based on John Dewey’s theory that students learn by doing. While at City-as-school, Basquiat created SAMO© - a fictional character who made his living selling a fake religion. He became close friends with graffiti artist Al Diaz , and they collaborated on the SAMO© (Same Old Shit) project - spray-painting aphorisms and philosophical poems on the D train of the IND line and around lower Manhattan.

“The stuff you see on the subways now is inane. Scribbled. SAMO was like a refresher course because there’s some kind of statement being made” (Al Diaz).

Basquiat's education finally came to an end at Al Diaz's graduation ceremony, where, on a dare, he dropped a box full of shaving cream on the principal's head - while he was speaking on the podium. After the incident, though only a year away from graduating, he felt that "there is no point in going back". A recurring subject in his life, Basquiat's fascination with stardom was only fueled when in 1970, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin - two of the many artists whose work and artistic achievements he greatly admired - died of drug overdoses at only twenty-seven.

“Since I was seventeen, I thought I might be a star. I’d think about all my heroes, Charlie Parker, Jimi Hendrix …. I had a romantic feeling of how people had become famous” (Basquiat).

Punk, New Wave and the Warhol Fantasy

While New York City was, on the one hand, crumbling in the late 1970s, it was also a free realm for alternative artists and creatives, on the other.

Pop is "doing the easiest thing; anybody could do anything," Warhol, who called his studio The Factory, had written. He had become the leader to thousands of kids with Bachelor of Fine Art degrees in the 1970s - an entire generation of would-be artists, rock-stars, dancers, and actors - who flooded New York. And, New York, with its cheap apartments, only a handful of homeless people in the streets, and no AIDS, opened its arms to welcome them.

A new Bohemia was happening - fashion, music, and art that produced a distinctive downtown aesthetic. Punk and the subsequent New Wave movements were quickly taking over. They were a much needed balm to the sterile Minimalist and Conceptual art that had dulled the art scene during the post-Pop decade.

In 1978, Basquiat lived in the East Village with Barnard biology graduate Alexis Adler, who documented his creative process. Because he had no money to buy canvases, he painted on the detritus found on the streets- tyres, doors, briefcases, as well as Adler's clothes, the floors, furniture, and the walls of the apartment. Speaking to Miranda Sawyer for the Guardian in 2017, Adler noted,

“He was a beautiful person and an amazing artist. I recognized that from the get-go. I knew he was brilliant. The only person around that time I felt the same thing about was Madonna. I totally, 100% knew they were going to be big.”

Away from home and trying to make some money, Basquiat started selling hand-painted postcards and t-shirts on the streets of New York. One day, he approached Andy Warhol and art critic Henry Geldzahler at the WPA restaurant in SoHo. Geldzahler quickly dismissed him for being "too young", but Warhol bought a postcard from him titled Stupid Games, Bad Ideas.

While a cultural aesthetic was flowering uptown, in the streets of Harlem and the basements of the South Bronx, Basquiat was becoming a regular appearance in the downtown scene. The Mudd Club, CBGB, Club 57, Tier 3, and Hurrah's were among the places he frequented along with David Byrne, Madonna, Blondie, Tina L’Hotsky, Diego Cortez, Ann Magnuson, and many other musicians, artists, and filmmakers.

During this time, an article was published in The Village Voice on the works of SAMO©. Shortly after, Basquiat and Al Diaz ended their collaboration. "SAMO is dead" started to appear on various SoHo walls, and, according to Diaz,

“Jean-Michel saw SAMO as a vehicle, the graffiti was an advertisement for himself. … all of a sudden he just started taking it over.”

Jean-Michel continued painting postcards and t-shirts. He even collaborated on many with Jennifer Stein and John Sex. The artworks were a combination of graffiti art and Abstract Expressionism, focused on consumer items such as Pez candy, baseball players, and the Kennedy assassination.

Musician, filmmaker, and band member of Basquiat's band Gray, Michael Holman, speaking to the Guardian, says,

“We were all these young kids in New York to carry out our Warhol fantasy, but instead of being a ringleader as Warhol was, we were in the band ourselves, making art ourselves, we were acting in films, making films, we were all one-man shows, with a lot of collaborations. That was the norm, to be a polymath. Whether you were a painter, an actor, a poet… you also had to be in a band, in order to really be cool.”

Being really cool indeed, Basquiat was, of course, in a band. In May 1979, along Michael Holman, Vincent Gallo and Shannon Dawson, he formed the band Channel 9, later renamed Test Pattern, then Gray, for which he played clarinet and synthesizers. The band performed a blend of jazz, punk and synth-pop, otherwise known as "noise music". Later that year, while wandering around The School of Visual Arts, Basquiat met fellow artists Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf. Him and Haring had an on-again, off-again relationship for the rest of their lives, with Basquiat admiring the raw, graffiti qualities of Haring's work.

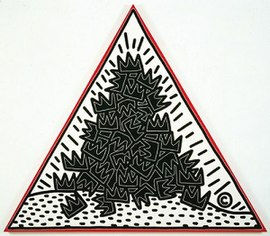

When Haring found out that SAMO was dead, he performed a eulogy at Club 57, and in 1988, as a memorial to Basquiat, painted A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Neo-Expressionism and Basquiat’s Times Square Show

In the eighties, Neo-Expressionism was all over New York. The role of art was now branched - it was seen as a vehicle for stardom and as a raw commodity. For the contemporary artist, success meant instant recognition, museum shows, magazine covers, and a lot of money.

By the end of 1979, Jean-Michel had met both producer of TV Party on New York cable television, Glenn O'Brian, and artist and filmmaker Diego Cortez. O'Brien frequently invited him to appear on the TV party, and Cortez first sold some of his drawings, and later introduced his work to art dealers - offering him a way into rich people's lives.

In June 1980, Basquiat's work was exhibited publicly for the first time in the "Times Square Show" - a group exhibition held in a vacant building at 41st Street and Seventh Avenue in the Times Square Area of New York. Organized by Lower East Side based artist-run group Colab (Collaborative Projects Incorporated), and Fashion Moda, the graffiti-based alternative gallery space in the South Bronx, it represented two very distinct subcultures: the downtown avant-garde consisting of Neo-Pop and New Wave, and the uptown avant-garde of graffiti and rap.

After the exhibition, Basquiat was one of the few artists mentioned in a review by Jeffrey Deitch for Art in America, which stated,

“A patch of wall by SAMO, the omnipresent graffiti sloganeer, was a knock- out combination of de Kooning and subway spray-paint scribbles.”

The same year, Basquiat was given a lead role in the film New York Beat Movie (eventually released in 2000 as Downtown 81). In it, though he clearly is the star, there are also cameos by Debbie Harry, Kid Creole and the Coconuts, Fab 5 Freddy, Lee Quiñones, and the band DNA. Basquiat, an artist himself, plays an artist who wanders the street in an effort to sell a painting so he can get enough money to move back into his apartment. He does sell it, but is paid by cheque, so he club-hops, trying to find a girl he can go home with. A familiar role to him.

New Art, New Money, and Hills of Drugs

In a matter of months, Basquiat went from being a penniless boy who did LSD and slept on the streets to being a really, really rich and famous artist. His drug abuse continued, only now, he had the money to buy more.

He was living in an apartment on 68 East 1st Street with his girlfriend, singer and artist Suzanne Mallouk. They met while she was bartending at Night Bird. Basquiat would come in and stand by the door, staring at her. Mallouk recalls,

“He wouldn’t come to the bar because he had no money for drinks. But then, after two weeks, he came in, put a load of change down and bought the most expensive drink in the place: Rémy Martin. $7!”

Eight months after that, money was coming in from everywhere. Basquiat would buy Armani suits by the dozen, leave piles of cash around the apartment, and throw parties with “hills of cocaine”.

Mallouk says,

“I watched him sell his first painting to Deborah Harry for $200, and then a few months later he was selling paintings for $20,000 each, selling them faster than he could paint them. I watched him make his first million. We went from stealing bread on the way home from the Mudd Club and eating pasta to buying groceries at Dean & DeLuca; the fridge was full of pastries and caviar, we were drinking Cristal champagne. We were 21 years old.”

What radically changed the art world and, perhaps, gave way to Basquiat’s rise, was of course, money. In the early 1980s, Wall Street's bull market produced an offspring: the SoHo bull market. New money was on the horizon, and it was increasingly being invested into art. By 1983, the art market in New York alone, was estimated at $2 billion. The new power players were now gallery dealers, barely distinguishable from their Wall Street clientele. Banks began accepting art as collateral for loans, and corporations began stockpiling important contemporary-art collections. Records were set at auction houses for everything - from $17 million for False Start by Jasper Johns, to$53.9 million for Van Gogh's Irises.

More stories like this:

In February 1981, Diego Cortez included Basquiat in "New York/New Wave," an exhibition for the large gallery space P.S.1, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, in Long Island City. Though the show included works by artists such as David Byrne, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andy Warhol, Basquiat was the one given high visibility. He had an entire wall on which he installed more than 20 drawings and paintings, catching the attention of art dealers Annina Nosei, Emilio Mazzoli, and Bruno Bischofberger.

Only a few months later, in May 1981, he had his first one-artist exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte in Modena, Italy. In September, Basquiat was invited by Nosei to participate in the group show “Public Address” at her gallery. Nosei, knowing that Basquiat did not have a studio, gave him her basement to use as one, which is where he met art collectors Herb and Lenore Schorr.

According to Lenore,

“We were very excited by the first painting we saw by him. This is not a common reaction, we’ve found, even now! He’s a very difficult artist for many, many people. But we just felt he was a wonderful, brilliant artist, very, very early.”

In an article titled “The Radiant Child,” which appeared in the December 1981 issue of Artforum, Rene Ricard noted,

“I’m always amazed by how people come up with things. Like Jean- Michel. How did he come up with those words he puts all over every-thing.? Their aggressively handmade look fits his peculiarly political sensibility …. Here the possession of almost anything of even marginal value becomes a token of corrupt materialism …. The elegance of Twombly is there but from the same source (graffiti) and so is the brut of the young Dubuffet.”

In early 1982, while living with Mallouk in an apartment in SoHo, Basquiat met Barbados artist Shenge Kapharoah. They became inseparable friends and collaborators, sharing interests in African ideologies and the concerns of artists within the African diaspora.

“You can see our friendship in the work. The paintings speak for them- selves … Moses and the Egyptians, Charles the First, lines like ‘most kings get their heads chopped off. ‘ This is what we were talking about,''

says Kapharoah.

Nosei organized Basquiat’s first one-artist exhibition in the United States in March 1982, and a month later, she arranged his first LA show at the Larry Gagosian Gallery. Paintings exhibited included Six Crimee, Untitled (LA Painting) - which Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa bought in 2017 for $110.5m - and Untitled (Yellow Tar and Feathers).

Through art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, Basquiat was later formally introduced to Andy Warhol. Immediately after the meeting, he made a painting of the two of them, and had it delivered to Warhol, still wet, only two hours after they’d parted.

The Radiant Child and His Indignity

Basquiat’s fame continued to rise, with him returning to LA in March 1983 for his second show in the Larry Gagosian Gallery. Regardless of his fame and importance, he still suffered the indignity of who he was - art dealers rejected him for being too young or too troublesome, for being a graffiti artist first, and of course, for being black.

He would leave successful opening parties, crawling with famous people, and could not get a cab. He would go out to dinner and restaurants would not let him in. It is no wonder that the paintings exhibited in his second LA show featured texts and images related to famous musicians, boxers, Hollywood films and the roles played by blacks in them. The works exhibited included Untitled (Sugar Ray Robinson), Jack Johnson, Horn Players, Eyes and Eggs, Hollywood Africans, and All Colored Cast (Parts I and II).

That same month, Basquiat was included in the 1983 Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Only twenty-two at the time, he was one of the youngest artists ever to be included in a Whitney Biennial. His two exhibited works were Dutch Settlers and Untitled (Skull).

Of the event, Warhol noted,

“We got tickets for the opening of the New Art show at the Whitney, the Biennial. And the show is just like the sixties …. These kids are selling everything-Jean-Michel Basquiat’s show sold out in Los Angeles”.

People were hungry for his art, and Basquiat obliged. He worked passionately, often on drugs. Film-maker Tamra Davis, who made the documentary Radiant Child (2009) says,

“He (Basquiat) was so charming, but it was also like hanging out with the Tasmanian devil. Everywhere he went, chaos would occur. You didn’t know what was going to happen next. It was invigorating, but it was also really tiring,” and, “He could make 20 paintings in three weeks.”

On August 15th, 1983, Basquiat moved into 57 Grace Jones Street, a building he leased from Warhol. Their friendship blossomed during that time. They worked together, painting each other's portraits, discussing philosophies of art and life, and attending art events. The whole world wanted a bit of Basquiat - the New York Times Magazine even featured him on its cover in a suit with his feet bare.

Black, Famous and Surrounded By White People

Basquiat, Warhol and Clemente spent a period working on collaborative paintings in New York. They completed fifteen paintings which, in September, were shown at the Galerie Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich. At the time, the show was not a success, with one critic even calling Basquiat Warhol’s “mascot”. According to Tamra Davis,

“He (Basquiat) really thought he was finally going to be appreciated. And instead they tore the show apart and said these horrible things about him and Andy and their relationship. He got really sad, and from then on it was hard to see a comeback. Anybody that you talked to that saw him around that time, he got more and more paranoid, his dread went deeper and deeper.”

As his dread went deeper, so did his addiction. He was at the peak of his fame and had shows all over the world, but Basquiat - the boy who produced art compulsively, out of, perhaps, his own deep-seated desire for approval - was not doing well. Which, again, brings me to his humanity. Dichotomic, like his work, one side shined brightly through his art and free expression. The other side, however, the one that had to be fueled by drugs in order to function, was only falling into darkness. Fame, money, and recognition were not enough - he was still carrying the burden of black manhood on his shoulders. Though the racism he faced was, at times, subtle, it still made its mark on his art. Ultimately, it went to his heart.

The pointed racial references in Basquiat's work are not enough to deny the fact that he was more in touch with white than with black culture. He rarely dated black women, just like his father.

He had only a few black friends and no black peers, so he found his heroes in jazz legends like Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday.

He was surrounded with white people.

“Being black, he was always an outsider. Even after he was flying on the Concorde, he wouldn’t be able to get a cab,”

says Fred Braithwaite.

The Boy Who Never Grew Up

In January 1987, Basquiat had a one-artist exhibition at the Galerie Daniel Templon in Paris. Twelve paintings were exhibited, including Gin Soaked Critic, Gri Gri, Mono, and Sacred Monkey.

However, when Andy Warhol died a month later, Basquiat was broken, perhaps, forever. According to Donald Rubell,

“The death of Warhol made the death of Basquiat inevitable, somehow Warhol was the one person that always seemed to be able to bring Jean- Michel back from the edge. Always when Jean-Michel was in the most trouble it seemed that Andy Warhol was the person who he would approach …. After Andy was gone there was no one that Jean-Michel was in such awe of that he would respond to”.

He became a recluse, and started to talk about doing something other than art: writing perhaps, or music, or setting up a tequila business in Hawaii. He did go to Hawaii in 1988, to try and get clean. Unfortunately, he did not.

In an article for Vanity Fair, Anthony Haden-Guest described Basquiat’s last night in detail: 12 August 1988, New York. Basquiat did drugs during the day, and was later dragged out to a Bryan Ferry aftershow party at bank-turned-club MK by his girlfriend, Kelly Inman, and another friend. He left shortly after, with his friend Kevin Bray. They went back to the Great Jones loft, but Basquiat was nodding. Bray wrote him a note, which said “I DON’T WANT TO SIT HERE AND WATCH YOU DIE”. He read it out to Basquiat, and left.

Jean-Michel Basquiat died on Friday, August 12, 1988, in his Great Jones Street loft. The autopsy report from the office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Manhattan Mortuary, listed the cause of death as “acute mixed drug intoxication (opiates- cocaine).” He was only twenty-seven.

“Jean-Michel lived like a flame. He burned really bright. Then the fire went out. But the embers are still hot” (Fred Braithwaite).

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Essential Books

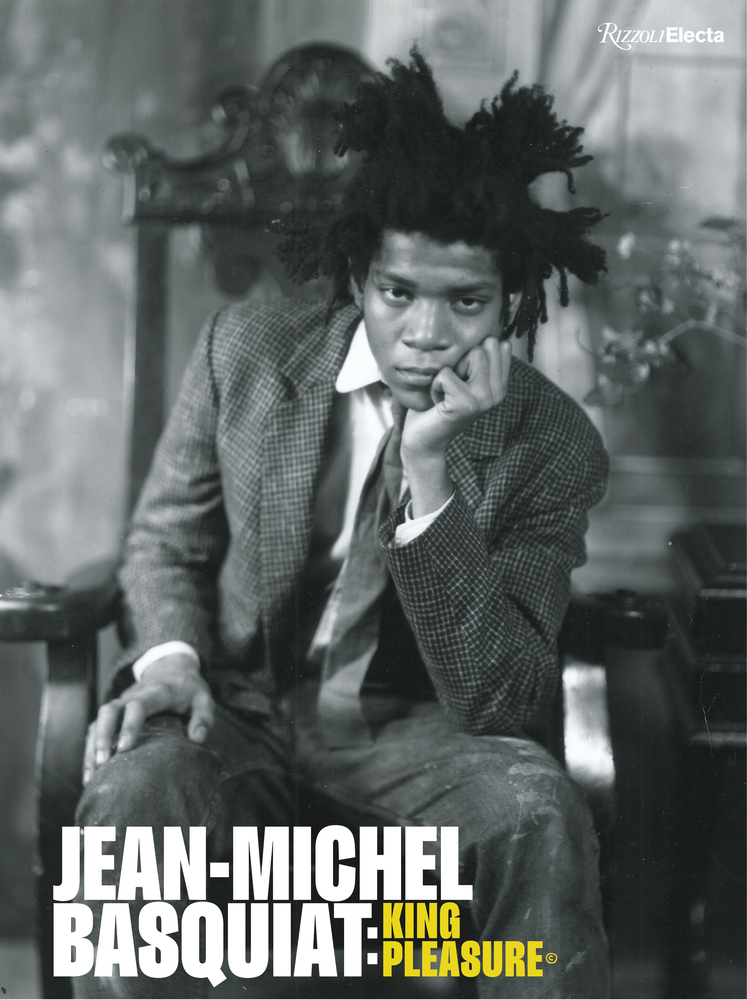

Jean-Michel Basquiat King Pleasure©

Exhibition Catalog

by Lisane Basquiat , Jeanine Herveaux, et al.

Description

courtesy of Bookshop.org

This landmark volume tells the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat from the intimate perspective of his family, intertwining his artistic endeavors with his personal life, influences, and the times in which he lived, and features for the first time work from the Estate’s largely unseen and significant collection of paintings, drawings, sketches, and ephemera.

Organized by the family of Basquiat, the exhibition and accompanying catalogue feature over 200 never before and rarely seen paintings, drawings, ephemera, and artifacts. The artist’s contributions to the history of art and his exploration into our multi-faceted culture—incorporating music, the Black experience, pop culture, African American sports figures, literature, and other sources—are showcased alongside personal reminiscences and firsthand accounts providing unique insight into Basquiat’s creative life and his singular voice that propelled the social and cultural narrative that continues to this day.

Structured around key periods in his life, from his childhood and formative years, his meteoric rise in the art world and beyond, to his untimely death, the book features in-depth interviews with his surviving family members.

Product Details

Publisher: Rizzoli Electa

Publish Date: April 12, 2022

Pages: 336

Language: English

TypeBook: Hardback

EAN/UPC: 9780847871872

Dimensions: 10.9 X 8.3 X 1.3 inches | 3.9 pounds

BISAC Categories: Arts & Hobbies, Arts & Hobbies, Arts & Hobbies

Jean-Michel Basquiat

by Eleanor Nairne (Author), Hans Werner Holzwarth (Editor)

Description

courtesy of Bookshop.org

The legend of Jean-Michel Basquiat is as strong as ever. Synonymous with New York in the 1980s, the artist first appeared in the late 1970s under the tag SAMO, spraying caustic comments and fragmented poems on the walls of the city. He appeared as part of a thriving underground scene of visual arts and graffiti, hip hop, post-punk, and DIY filmmaking, which met in a booming art world. As a painter with a strong personal voice, Basquiat soon broke into the established milieu, exhibiting in galleries around the world.

Basquiat's expressive style was based on raw figures and integrated words and phrases. His work is inspired by a pantheon of luminaries from jazz, boxing, and basketball, with references to arcane history and the politics of street life--so when asked about his subject matter, Basquiat answered "royalty, heroism and the streets." In 1983 he started collaborating with the most famous of art stars, Andy Warhol, and in 1985 was on the cover of The New York Times Magazine. When Basquiat died at the age of 27, he had become one of the most successful artists of his time.

This book allows an unprecedented insight into Basquiat's art, with pristine reproductions of his most seminal paintings, drawings, and notebook sketches. In large-scale format, the book offers vivid proximity to Basquiat's intricate marks and scribbled words, further illuminated by an introduction to the artist from editor Hans Werner Holzwarth, as well as an essay on his themes and artistic development from curator and art historian Eleanor Nairne. Richly illustrated year-by-year chapter breaks follow the artist's life and quote from his own statements and contemporary reviews to provide both personal background and historical context.

Product Details

Publisher: Taschen

Publish Date: October 09, 2018

Pages: 500

Language: English

TypeBook: Hardback

EAN/UPC: 9783836550376

Dimensions: 18.1 X 12.4 X 3.2 inches | 12.6 pounds

BISAC Categories: Arts & Hobbies, Arts & Hobbies, Arts & Hobbies

--

If you liked this story, sign up for our newsletter – a special selections of articles, artist features, interviews, videos, short films and more, delivered straight to your inbox.

For more stories and updates from A RAY OF SIGH, follow us on Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook.

A RAY OF SIGH is part of the Bookshop affiliate program and may earn a commission from qualifying purchases.

#arayofsigh #arayofsighblog #jeanmichelbasquiat #basquiat #basquiatart #basquiatpaintings #SAMO #andywarhol #keithharing #popart #neoexressionism #newwave #punk #newyorkcity #newyorkcityartmovements #artmovements #contemoraryart #contemporaryartists #contemporarypainters #contemporarypaintings #thefactory #painting #painters #art

Comments